The author makes the radical suggestion that the retirement age of judges may be increased …. but wait …. there’s a catch! …. He wants their right to practice before the lower courts to be taken away! Any takers for this suggestion?

1. At present the judges of the Apex court retire at the age of 65, whereas the judges of High Courts and the members of the ITAT retire at the age of 62. Most of the judges of the Apex Court even after retirement render service to the nation by chairing various forums, like Authority for Advance Rulings till the age of 68. Similarly the judges of the High Courts also serve as chairman, president or members of various quasi-judicial forums, like, Administrative Tribunals, Customs Excise and Service Tax Appellate Tribunal, SEBI Tribunal, etc., where the age limit is 65. When the judges can render service as chairman of various forums and render the Judicial service which they were rendering earlier on the bench there is no reason why the age limit should not be raised. If the Government can retain the services of judges for another three years, it will be a great service to the nation and the pendency of cases before High Courts will reduce.

2. In India many professionals join the judiciary with the intention of serving the nation and not with the intention of getting a permanent job in the Government. A fresh law graduate when he joins a multinational gets much more than a sitting judge of High Court, who may have put in more than 20 years of practice in law. Experience of a judge and his knowledge is an asset to the justice delivery system; hence it is in the interest of the nation to raise the age limit of judges.

3. At the inaugural function of the ITAT Tribunal Member’s Conference at Mumbai in the year 2006 the Hon’ble Law Minister H. R. Bharadwaj stated that he is in favour of raising the retirement age of members of the ITAT. But, till date there is no more in this direction.

Federation is of the considered opinion that this is one of the important judicial reforms which is need of the hour. It is important to retain the knowledge and experience of the judiciary to deliver speedy justice.

4. The sanctioned strength of the judges of the Apex Court is 26, that of High Courts 749 and members of the ITAT is 126. Hence, it cannot be viewed as a vast opportunity in the employment sector yet retention of less than 1000 persons will have multiplier effect on justice delivery system. In Australia Judges of Federal Court and Supreme Court retire at the age of 70. Similarly in Japan judges of High Court retire at the age of 65 and Supreme Court at the age of 70.

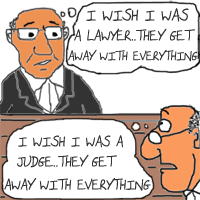

5. We are of considered opinion that when the age limit of members is increased the retired members may not be permitted to practice before the same forum or forum lower to the Tribunal. When a retired member appears before the authorities lower to the Tribunal, the institution of the Tribunal loses the respect of the people. The High Court judges after retirement never appear before High Court or lower courts, this has enhanced the respect of the judiciary. It is essential that the service rules may be amended or by convention the retired members may not be permitted to appear at the place of retirement or any forum lower to the Tribunal.

6. It is time to initiate debate on the proposal of the increase of the age limit of the Supreme Court judges from 65 to 68, High Court judges and members of the ITAT from 62 to 65. The Federation has sent a representation earlier to increase the age limit of judges of Apex Court, High Courts and Members of ITAT.

A thought for debate and consideration.

Dr. K. SHIVARAM

Editor-in-Chief AIFTP

(Reproduced with permission from the AIFTP Journal – September 2008 issue)

Even if Govt service is not a contract and is actually a status ,a vested right cannot be taken away by retrospective legislation as held by the Honble’ Supreme court in the case of Union of India vs. Tulshar RanjanMohanty and Others(1995 Air SCW 1758) . The apex court considered retrospectivity of legislation in the case of k s paripoornan vs. State of Kerala(Air 1995 Suprme court 1012).The decision of the apex court in the case of Indian Council of Legal Aid vs.Bar Councilof India is also relevant.

Government service is a contract, however noble it is. Prohibition to practice before the Tribunal retrospectively for a retd. Member is a breach of the contract. It is divestment of a vested right. Many Members might not have joined if the prohibition was there initially.

Comparison with High Court judges is comparing dissimilars. They are closer to Commisioners.

Retd. Members are a good addition to the bar. Their entry is in public interest as it provides more choice in a relatively closed field. The bar should welcome their entry instead of resisting it.

In view of the increased average life span, legitimate means of making income after retirement should not be barred. Barring such means will have adverse social and other consequences which need not be mentioned.

The voice of Mr.Tapas Ram Misra is sane and deserves to be heard by the authorities.

Dear Sir,

I am partly in agreement with your suggestions. Raising the age limit of judges and Tribunal members is a welcome suggestion, especially in view of the dearth of judges and members and in recognition of their valuable knowledge and experience.

At the same time, I find it difficult to bring myself in agreement with the suggestion with regard to retired members’ right to practice before the forum of which they were a member. This becomes pertinent today in view of the notification amending the rules and disentitling retired ITAT members from practising before that Tribunal, and of the recent High Court decision affecting CESTAT members in the same way.

Since it is not suggested anywhere that this suggestion aims at reducing competition for practising members of the Bar (who have never been members of the Tribunal) we shall not discuss that at all. The only remaining argument deals with the prestige of the Institution.

That raises an all important question: Is the Instiution not greater than the individuals officating it for a particular period of time? The other question is; are we all not intended to be equals under the Constitution? Let us deal with each one.

So long as a person is a judge or member of a Tribunal he is bound by a clear code of conduct, and has a well defined role to hear both parties before him and reach a judgment without fear or favour. Once such a person retires, he becomes an ordinary citizen of the country. He may be a plaintiff/appellant or a defendant/respondent before any court or tribunal, and has to be dealt as any other litigating party would be. Any objection to such a person appearing as an advocate or practitioner before that court or tribunal would be prompted by an assumption that he may be treated differently (may be with greater respect or patience or fellowship) than another advocate or practitioner. Such an assumption, in my humble submission, is an affront to the high integrity shown by these courts and tribunals.

Admittedly, High Court judges do not appear before the High Court after retirement. But this fact, in my experience as an advocate for almost twenty years, has never been the ’cause’ of my reverence for the High Court. That reverence arises from the ability of our High Courts to deal with litigants and their counsel irrespective of who they are. On the other hand, the fact that retired members of the ITAT have been practising before the Tribunal has never for a moment diminished the prestige of the Tribunal in my eyes. The conduct of past members and their ability has been exceptional and the respect they’ve received from the bench and the bar has always been reflective of this ability and conduct. Anyone falling short in these areas has been dealt with sternly by the benches.

In fact I’ve always been baffled by the question, is a retired judge of a High Court too big for the High Court and a retired judge of the Supreme Court too big for all judicial bodies including the Supreme Court itself, so that they have to be restrained from practising before these courts so as to preserve the honour of the court? Is it more honourable for the sysytem to encourage retired judges to head different regulatory and quasi judicial bodies and to act as arbitrators rather than allow them to become ordinary citizens with ordinary rights including the right to practice as advocate before any court?

If a legislator (MP or MLA) can practice as an advocate while being a legislator, and an executive-cum-legislator (a minister) can practice as an advocate beofre any court after ceasing to be a minister, why should a member of the judiciary be treated differently?

In my humble submission, if we have to strengthen our institutions, we will have to ensure that a chair is always bigger than the man temporarily occupying that chair. Teen Murti Bhavan at Delhi is a constant reminder of how, by treating the occupant of the Prime Minister’s chair (with due respect to his greatness otherwise) to be greater than the chair itself, the designated residence of Prime Minister of India was converted to a museum dedicated to an individual.

I hope that the new notification and the prevailing judicial view on this issue is seriously reconsidered.